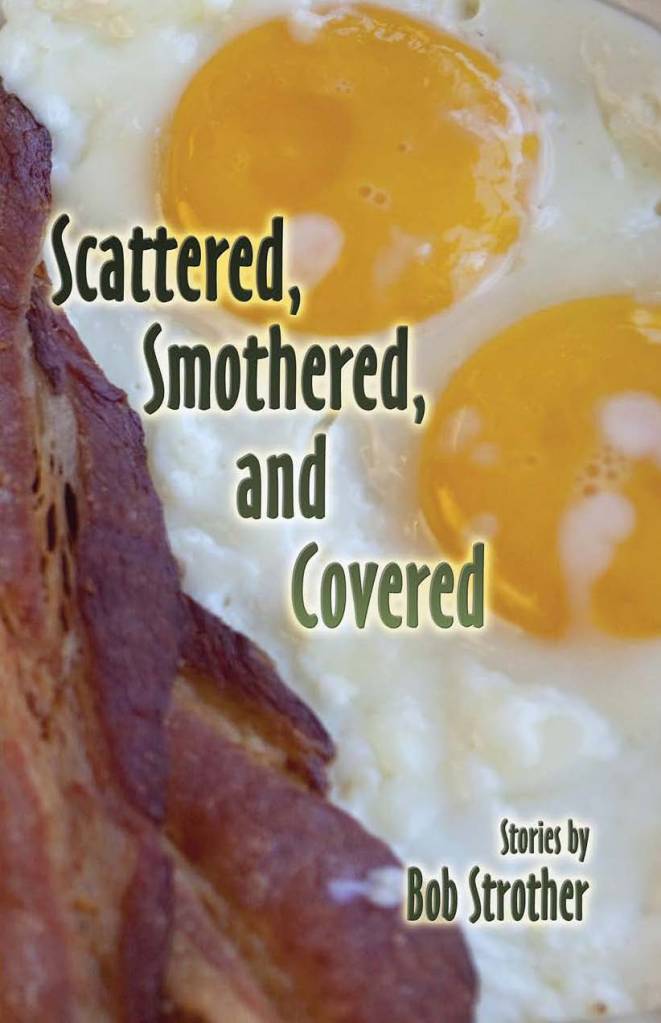

SCATTERED, SMOTHERED, AND COVERED

Fiction, ISBN: 978-1-59948-276-7, 284 pages, $14.95

Bob Strother serves up a heaping helping of short stories in a collection which defies easy categories, with vampires, cheerleaders, debutantes, ghostly little girls, hitmen (and women), Ma Barker, a Marine gunnery sergeant with his own unique method of rehab, and my personal favorite—a septuagenarian soviet sniper who takes the theft of her welfare check unkindly.

Well-crafted, with sharply drawn characters, wry wit, and a touch of darkness, these stories breathe with a depth and fondness from Bob’s own heritage.

— David Weber, best-selling author of the Honor Harrington series

WEB DISOUNT: $10.00 (+ shipping)

Shipping outside U.S. incurs additional charges.

Purchase: Scattered, Smothered, and Covered

This is a smart collection. Strother is at his best when he choreographs the dance between a man and a woman: from Zelma and Jeff, teenagers teaching each other to kiss in “Baby Don’t Say Don’t” to the burglar, Brody, held at gunpoint by the old woman he’s robbing in “Sniper.” The faces are familiar, but Strother effectively surprises and unnerves. A clever and engaging read.

— Carla Damron, author of Death in Zooville, A Caleb Knowles Mystery

PUBLISHED SHORT STORIES SAMPLES

Below are previews and links to some of Bob’s favorite short stories, published in various journals over the years…

The following pieces first appeared in moonShine review:

Blind Billy’s Bayou

Blind Billy leaned back on the canvas-topped folding stool and rested his shoulders against the rough brick marking the mouth of the alley. Then he slipped off his battered fedora and let the late afternoon sun warm the furrows of his face. His mind wandered, as it often did lately, to a faded photograph taped to the dresser mirror in his bedroom. It showed a pretty black woman in her early twenties, one arm around a small, smiling boy perched on her cocked hip. She stood on a dock, somewhere on the bayou. Tall cypress trees rose high over the water, their fine tree branches spreading like filigree against a sun hanging low over the horizon.

A coin clinked in the tin cup at his feet and ended his reverie.

“Afternoon, Billy,” a man said.

Billy doffed the fedora again, leaned forward, and his fingers automatically strummed a chord on the guitar he’d owned since he was in his teens. “Thank you, suh,” he said, using a thumbnail to pick out the first few notes to a blues song. But the man had already started away. Most did. Hardly anyone actually stopped long enough to hear him play.

Blind Billy wasn’t really blind, but he wore the dark glasses anyway. They went with his character, and at age seventy-six, he guessed it wasn’t much of a lie, since he truly didn’t see all that well. He lived two blocks away, down the alley and across the street in an area spotted with tar-paper shacks and scraggly yards, clotheslines bowing under the weight of diapers, yellowed underwear, and sheets thin enough to see right through …

Click here to read full story…

Madison 2-Forever

Roger Dougherty caught a glimpse of his humped shadow on the hallway wall and immediately looked away. Gnome, he thought. And then he smiled. Not at his grotesque, arthritic image, which had sent more than one Trick-or-Treater scurrying wide-eyed back to mommy, but because he had remembered an appropriate word. He said the word aloud: “Gnome,” then, “troll,” then … that was as far as he got. Arthritis and Alzheimer’s—another big double “A” battery that kept going and going and going. He could recall the propeller beanie he’d worn as a child but not where he’d hung his hat the previous evening.

Roger found himself staring at the cell phone on the table where he kept his house keys, mail, and a collection of other household objects whose proper place he had forgotten. Some he might remember later. The rest his daughter, Kelsey, would replace when she came by to check on him Sunday afternoon.

He had been about to make a phone call, but why? With a sigh and a grunt, Roger shuffled back to the kitchen and checked the list thumb-tacked to the corkboard hanging by the cabinets. His finger traced a trembling path down the list, hesitating here and there, and finally coming to rest on the number for the local grocery. A minute’s fumbling through his pockets produced a wrinkled scrap of paper and a scrawled list of necessities. Keeping the list in his hand, Roger made his way back to the hall table, picked up the phone, and consulted a taped-to-the-table set of instructions Kelsey had prepared for its use …

The following piece first appeared in Southern Writers Magazine:

(NOTE: No longer in publication)

The Peanut Man

In those days, long before shopping mall was part of our vocabulary, big-city downtowns were vital, bustling places that teemed with retail, commerce, and entertainment venues. Movie theater marquees boasted Hollywood’s best in flashing lights, department stores perched on every corner, their windows filled with the season’s latest fashions, and a Krystal burger, served on a porcelain plate, could be purchased for a nickel.

It all seemed so unbelievably big. I suppose, when you’re five years old, everything seems big, but this was different. It was the first time I’d gone downtown with my mother, and it was like being enveloped in a whole new world of heady sensations.

The sidewalks swarmed with people—a kaleidoscope of continuous movement, like ants swarming on a kicked-over anthill. Cars filled the streets, and not the sleek, finned, pastel-colored ones that came later in the decade. These darker, portentous cars, with teeth-like grillwork, looked more apt to pounce than take flight. The sweet, rumbling hum of their motors washed over the streets, interrupted only by the occasional blare of a horn or the dry-bones rattle of diesel-powered buses.

Rushing together down the sidewalk, my small hand held tightly by her larger one, the passing windows melted into a blur of color. The air, redolent with exhaust fumes, also carried the more delightful promise of popcorn, coffee, and onions frying—a mélange of street-side fragrances forever and indelibly stamped upon my sensory memory banks.

It was no different with the Planters’ Peanut Man.

My nose detected the aroma of roasting nuts at least three storefronts away. Slightly sweet, undeniably nutty, and tanged with salt, the smell alone almost stopped me in my tracks.

What came next actually did.

My mother yanked me from the streaming pedestrian traffic just in time to keep both of us from being trampled. Hardly aware of it, I stared gaping and awe-struck at the costumed figure on the sidewalk. His head and torso were the dimpled likeness of a peanut. Black shirt and slacks, white gloves and spats, a top hat and monocle completed the elaborate outfit.

I glanced up at my mother and she smiled at me. When I returned my gaze to the peanut man, he had bent down toward me, holding a spoonful of nuts.

“Hold out your hand, Charlie,” my mother said.

As I did, the costumed figure filled my palm with half a dozen red-skinned, roasted peanuts, which disappeared into my mouth like dust bunnies into my mother’s Electro-Lux. Then he handed some to my mother. She thanked him nibbling a few. “I can never stop with just a few, Charlie. I guess we’ll just have to go inside and buy a bag.”

The peanut store was narrow and long, with roasters along one wall, fronted by a glass case brimming with the most amazing array of nuts I’d ever seen. Customers jostled each other inside the confining space, handing over coins and bills before hurrying back outside with their salty treasures.

A mostly bald man dressed in white looked over the glass case and down at me. “What’ll it be, young man?” …

The following piece first appeared in The Petigru Review:

Light Captured

Joss Richards studied his younger brother, Leslie, who sat opposite him at the breakfast table, vacant-eyed and slumped over a bowl of rapidly cooling Cream of Wheat. The kitchen smelled faintly of last night’s dinner: liver and onions. On the wall over the refrigerator, a yellow cat-clock ticked, its pendulum tail whisking away seconds and minutes. It was another cold December morning in 1959. Joss’s parents, both third-shift workers at the Dixie Yarns plant, snored in their bedroom as the boys breakfasted before leaving for work and school.

Joss turned on the small Zenith radio next to the sink, keeping the volume low. Clyde McPhatter’s voice floated through the room, crooning his latest hit, “A Lover’s Question,” and Joss hummed along as he rinsed his bowl and coffee cup. Finished, he turned back to his brother.

As always, facing the prospect of another day at Eastside High, Leslie wore his usual forlorn look. This morning, the younger boy’s despair evidenced itself more than normal. Worry lines etched Leslie’s shiny brow, and his already thin lips suggested a wound more than a mouth.

Joss winced just looking at him. No ninth-grader should ever have to wear such a pained expression. He snapped his fingers in front of Leslie’s face. “Earth to Leslie; what’s up, kiddo?”

Leslie looked up, blinked twice. “It’s rope day.”

Joss nodded. Enough said. Having graduated the previous year, he knew all too well. All Eastside students had to take gym class. No exceptions. Except for those visibly impaired, which pretty much meant you either came to school in a wheelchair or you took gym.

Leslie wasn’t impaired, just under-muscled and overweight.

“I’m fat and slow,” he said. “I’ve spent the last four months running back and forth across the gym basketball court and praying I’d never have to actually touch the ball. I’ve been lucky so far. The other kids barely know I’m there.”

Rope day presented a very different kind of challenge. Once a month, the gym teacher, Mr. Howell, dragged out the knotted, rough rope and secured one end to the gym’s ceiling trusses. Each kid—girls excepted, everyone knew they had no upper body strength—struggled up the rope to the topmost knot some twenty-five feet above the polished hardwoods.

According to Leslie, he had tried on three prior occasions. Each time, he failed to make it more than a few feet. It always ended with Leslie collapsed in a trembling, sweaty heap on the floor, red-faced and short of breath. Even with the blood rushing through his head, he still heard the snickers of the other kids.

Joss stood behind Leslie and massaged his shoulders. “It’s only one day. By this time tomorrow, it’ll all be over with.”

“Not the laughing. Nobody talks to me. But they all laugh at me. It never stops.”

Joss worked split-shift in the mailroom of Interstate Life Insurance, nine to two. He had a three-hour break before returning to finish out his shift from five to eight. Leslie’s gym class was last period. He could easily be there for the class and then back at work before five.

“Tell you what, kiddo. How about I come to your gym class? I’ll cheer you on, and no matter what happens, I’ll make sure nobody laughs.” He pounded his fist into the palm of his other hand for emphasis.

A smile almost made it through Leslie’s gloomy visage. He looked up at Joss with big, moist, grateful eyes. “You’d really do that?” …